A matter of grit: Do you show grit? Or quit?

“Effective building – of bridges, of concepts, and ideas – comes from a more supple form of grit that knows when development needs to give way to discovery.” -Sarah Lewis

In the pursuit of achievement, what matters more-IQ or grit?

In her book The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure and the Search for Mastery, Sarah Lewis tells of the rather common phenomenon that somewhere in the world, roughly every 30 years, a major bridge collapses while it is still being erected, or soon afterward. Why? When scientists evaluated what was behind this curious phenomenon, they found it was not (1) the implementation of new technology or (2) the lapse in an engineer’s structural analysis. Rather, “the ongoing pattern of collapse occurs…because of the blind spot created by success.”

That is to say, when engineers are one professional generation removed from the original foundational design, as Lewis states, “they tend to trust their models too much.”

How do we balance what we know too well with what we might discover if we looked at familiar territory in a new way?

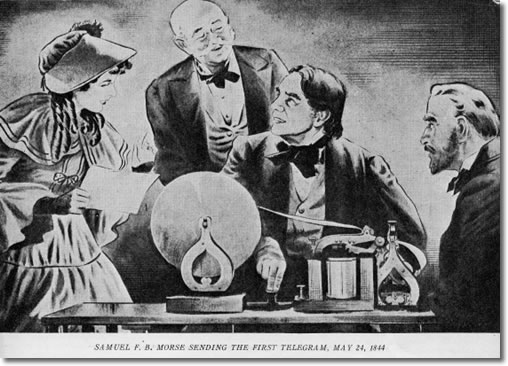

Lewis tells another story about Samuel F.B. Morse, inventor of the telegraph. Morse desperately wanted to be a painter and worked ardently, but

unsuccessfully, for more than a quarter-century on that goal. But then, on one day, Morse turned his canvas upside down-constructing his first model telegraph out of cogs and clock springs and setting into a wooden frame-the abandoned canvas stretched taut for a painting he would never complete. According to Lewis, Morse “took what he learned [in painting] to pioneer the invention of the telegraph, the device that would transform communication around the globe. The telegraph-from the Greek words tele and graph meaning “to write at a distance”-served to annihilate space and time.

What was it that caused Morse to stick to his task of painting for 25 years (show grit) and then somehow know when to quit and go in an entirely new direction?

Lewis, fascinated by the “psychology of effort,” visited Dr. Angela Lee Duckworth at the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania to explore the question: “What are the true barriers to achievement?” According to Duckworth and her team, they see three barriers: (1) adversity-things implode, break down or catastrophe strikes (2) failure-a hardship for which you are largely responsible or (3) the plateau, where everything seems to stall, that moment when you do not know what to do next. Your reaction to that plateau is a barometer measuring grit.

Duckworth has studied grit in a variety of environments-Teach for America; Scripps National Spelling Bee; the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. She found that grit has no correlation to IQ, and how we respond to failure reveals grit. Do we take failure personally and see it as a comment on our identity, or do we look at it as feedback about how to move forward?

What is grit? According to Lewis, grit is not “a simple elbow-grease term for rugged persistence. It is an often invisible display of endurance that lets you stay in an uncomfortable place, work hard to improve upon a given interest, and do it again and again….Unlike dysfunctional persistence, a flat-footed posture we ease into through the comfort of success, grit is focused moxie, aided by a sustained response in the face of adversity.”

A key component of grit is developing the ability to cope with failure. Harvard University President Drew Gilpin Faust said recently that “we need to make it safer to fail. Harvard students are good at performing in areas in which they excel. Learning how to fail is against their understanding of themselves.”

Duckworth has noticed that while there has been an upturn in self-esteem among students in the last two decades, achievement has not kept pace with self-esteem. Duckworth says “many American kids, particularly in the last couple of decades, can feel really good about themselves without being good at anything.”

The Fins have coined the word “sisu” referring to the intestines or the idea of “having guts.” In Finland, sisu is part of national identity, forged by their history of war with Russia in combination with a harsh climate. Finland is ranked No. 1 in the world for its education, ahead of Korea. There is no magical pedagogy or elaborate after-school tutoring in Finland. In fact, Duckworth attributes its success to the fact that the Fins combine sisu with creative play.

While grit is showing up again and again, it is also having the insight about when to quit. According to Duckworth, “high-functioning people” can eventually judge when to change direction-this happens with lateral thinking. Grit is more than persistence. It involves the ability to think outside of the walls of a discipline, to shift the frame of view from a close-up to an aerial view, from convergent thinking to divergent thinking, merging play with innovation.

Other researchers agree with Duckworth on the idea that to teach grit, mentors and teachers must help students understand that, above all, “there is no linear path.” In most schools, the main way to accomplish this is through the arts-the very thing that’s has been virtually eliminated from most American public schools.

Lewis: “As the arts are eliminated, so is the avenue to one of their irreplaceable gifts: the agency to withstand ambiguity long enough to discern whether to pursue a problem or to quit and reassess-when to see, as Morse did, that the painting could also be part of a telegraph….If we are low in grit, as well, we are less able to stay with these problems long enough to solve them.”

Another invaluable aspect of the arts is the critique, and teaching students to learn how to benefit from constructive criticism. Lewis likens criticism to a circle. There is a myth about the West African trickster diety Eshu-Elegba, bisected by a line from forehead to spine, so that half of his body was red, the other white. Some of the people thought he was red; others, white. The whole truth could only be ascertained by walking the circle to encompass the whole view.

Morse’s story is an argument for science and art to be joined once again because they belong together. Lewis argues for invention itself. “Inventions come from those who can view a familiar set of variables from a radical perspective and see new possibilities….It lets us shift our frame, like a painter who stared at a set of canvas stretcher bars for years and one day saw its potential to be an original communication device. And then persisted for decades to realize its full application for the world.”

Morse eventually referred to his telegraph as part of the “Arts” of this country. Finding “the art” in something not only allows us to create something from nothing, it allows us to transform what may at first appear to be the ruins of failure into something worthwhile.

Quincy Whitney is a career journalist, biographer and poet. Contact her at quincysquill@nashuatelegraph.com or quincy@quincywhitney.com.