Recalling the shock and sadness of 1949

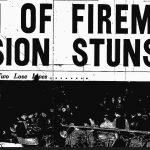

The front page of the Jan. 13, 1949 Telegraph reports the tragic news of the night before.

- The front page of the Jan. 13, 1949 Telegraph reports the tragic news of the night before.

- COURTESY PHOTO The Nashua fire engine known as Hose Company 1 out of Amherst Street station lies on its side against a bus following the crash that killed two firefighters and injured two others in January 1949.

But roughly a dozen years later, after bouncing back from the one-two-three punch, then getting the news that would force many Nashua families to bid a tearful goodbye to a son, brother, father or uncle as they headed to war, then a few years later joyously welcoming the lucky ones home while mourning those who didn’t make it, Nashuans were sent reeling by what the Nashua Telegraph would call “a three-day period of unspeakable tragedy.”

All but unheard of, especially in comparison to the “Disaster Decade” of the 30s, this dreadful spate of shock and sadness began just 10 days into 1949, and by the time it was over, seven people, including a pair of “popular, well-respected” Nashuans ages 21 and 22, were dead.

I’m most familiar with the second of the three tragedies, having noted it numerous times in “on this date in …” social

media posts and when talking Nashua fire history.

COURTESY PHOTO The Nashua fire engine known as Hose Company 1 out of Amherst Street station lies on its side against a bus following the crash that killed two firefighters and injured two others in January 1949.

A photo, one of a couple dozen my fellow historian Charlie Colletta – French Hill history is his specialty – lent me the other day got me thinking about that tragic evening some 70 years ago last month.

Just before 9 p.m. Wednesday, Jan. 12, the bells began clanging at Nashua’s four fire stations, striking the box number nearest the old St. Jean Baptiste building on Chestnut Street.

At Amherst Street station, the city’s second-eldest fire house, firefighter Otis Mason, 38, slid behind the wheel of the aging, open-cab pumper designated Hose Company 1 and pushed the starter button.

Capt. Alfred Laplante, the 48-year-old station officer, climbed into the seat aside Mason, while firefighters George F. McCaugney, 33, and Albert Winterbottom, 40, stepped onto the truck’s rear platform, called a tailboard, and pulled into place the long, metal safety bar.

They could see heavy smoke filling the sky as they rolled out of the station and down Library Hill. The truck’s lights flashing and siren screaming, Mason was guiding the lumbering vehicle south on Main Street when a car suddenly emerged from Temple Street, and right into the truck’s path.

Mason, according to various reports, did his best to avoid the car, but to no avail. The vehicles collided in the middle of the intersection, the “terrific impact … sent the heavy fire truck rolling over several times, dashing two firemen to their deaths,” the Telegraph reporter wrote.

The truck came to rest up against a Hudson Bus Lines passenger bus, but luckily for the passengers, it only nudged the bus slightly.

Mason, Winterbottom and the driver of the car were seriously hurt and rushed to the hospital.

But Laplante and McCaugney, who ended up trapped under the wrecked truck, probably died instantly; they were pronounced dead a short time later at the hospital.

Meanwhile, the blaze, which was thought to have started in the rear of City Cash Market on the ground floor, had escalated to general alarm status as crews, likely not yet aware of their fellow firefighters’ fate, rescued several people from apartments on the upper floors while fighting the blaze.

The third tragic death came right around the time the two firefighters were killed. A night watchman at the former Textron, part of the Millyard complex, was reportedly on his way to the mill’s roof to watch the fire when, the Telegraph reported, “he stepped into an open elevator shaft and plunged to his death.”

Tragedy number four in what I call “The Three Days that Stunned Nashua” came the next day. A Manchester man was fatally injured when his car struck a tree on the Daniel Webster Highway.

It was two days earlier, on “a bleak, Jan. 10 afternoon,” the Telegraph reported, that this unfortunate trilogy of tragedy began.

Robert “Bobby” Bellavance, 21, and Everett “Bull” Martin, 22, were up in a Piper Cub not far from the Nashua airport when, as described by the Telegraph, “their plane, rented from Nashua Aviation and Supply, struck the tops of two tall trees … (and) like a huge yellow bird being clipped by a sharp instrument, was literally dismembered in its downward flight through the thick woods” off Route 101A.

Bellavance, hailed by The Telegraph as “one of the greatest football players to don the Purple,” also starred in baseball and hockey. He graduated from Nashua High in 1947, and was weighing whether to go to St. Michael’s College in Vermont or Temple University.

Martin, born in Milford, was “known as ‘Bull’ to his many friends,” The Telegraph reported, and was “a sports-loving fan (who) participated in various sports.”

Both men worked for the Nashua Gummed and Coated Paper Co. – later Nashua Corporation – and decided to rent the plane “for a half-hour’s ride in the clouds.”

The Telegraph reported in great detail the rescue operation, which, in a sign of the times, was populated more by civilian volunteers than police, fire or other “official” personnel.

The story said Telegraph “personnel” also joined in the search, and “fouond parts of the aircraft scattered all about … a wheel here, part of a wing 50 feet away, other pieces strewn about.”

Bellavance and Martin were killed instantly, their bodies found under the wreckage of the plane.

Searchers used as a guide the old rail tracks running parallel to Route 101A, then called “the Milford road.”

Police officers Mike Patinski and John Barry reached the wreckage first, about the same time that Sid Clarkson, a flight instructor with H and H Airways, located the site from the air.

The plane crashed “about a mile northwest of the Cadorette Farm” in “heavily wooded terrain,” The Telegraph reported.

The search and the realization that two popular young men lost their lives in such tragic fashion soon took on another layer of shock and grief, when a man named Victor Berube suddenly “called for a stretcher.”

Berube, who The Telegraph called “well acquainted with this region,” had come upon a man lying on the ground in the woods. He was a member of the rescue party; he was also unconscious and unresponsive.

A few minutes later, when Berube “emerged from the forest” and informed search leaders “an unidentified man was dead,” according to The Telegraph, “the group remained stunned – unable to believe it.”

Dean Shalhoup’s column appears Sundays in The Telegraph. He may be reached at 594-1256, dshalhoup@nashuatelegraph.com or @Telegraph_DeanS.